- Home

-

Shop All

- Bible Verse & Christian

- Black & White Art Prints

- Book Lover Quotes

- Feminist Quotes

- Book Quote Mugs

- Fine Art Quote Prints

- Inspirational Wall Art

- Jane Austen Quotes Prints

- Jane Eyre & Bronte Art

- Love Poems & Quotes

- Minimalist Art Prints

- Nursery Decor Prints

- Other Options & Custom

- Poetry Quote Art

- Shakespeare Quotes Prints

- Travel Quote Art

- About

- Blog

- Track Order

- Contact Us

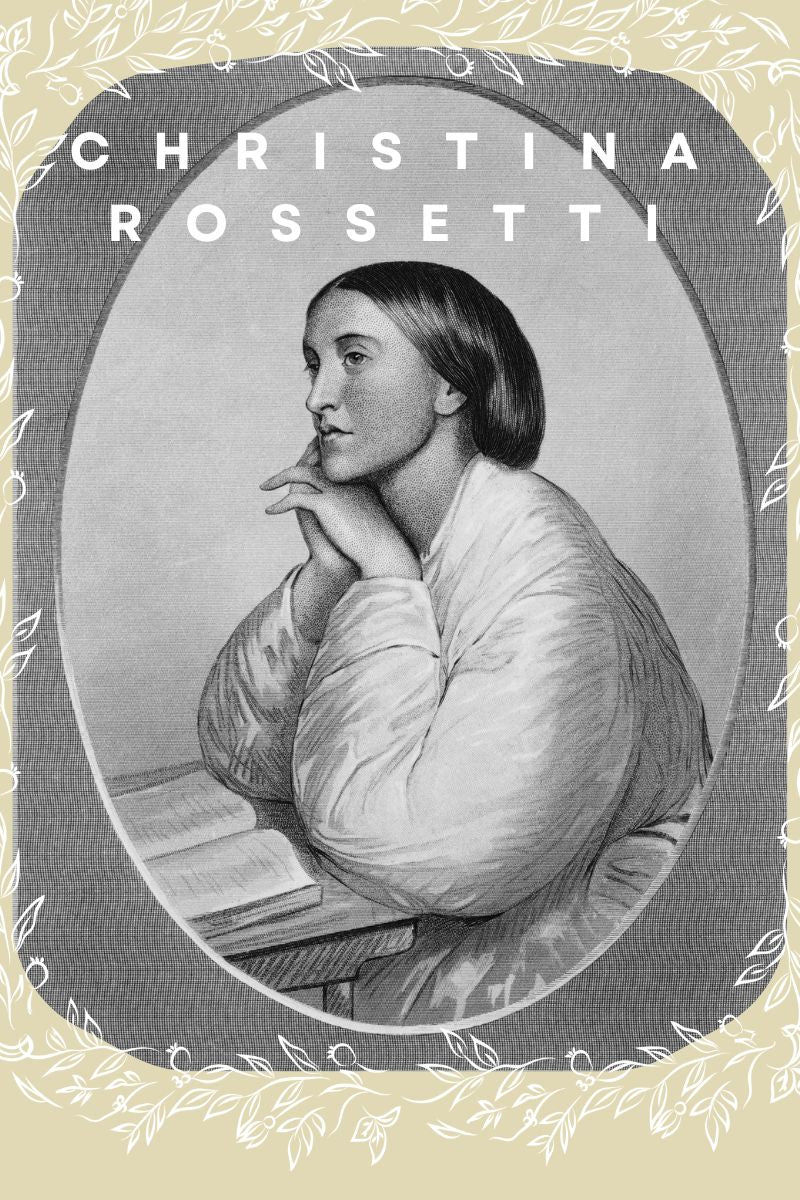

Christina Rossetti: Britain’s Most Imaginative Poet

Rossetti wrote wild, romantic and imaginative poetry that leaps off the page. Whether it’s her weird and wonderful epic poem, “The Goblin Market” or her beautiful, mysterious sonnets like “Remember”.

While her poetry still looms large in anthologies and collections of British poets, her own life was quieter, more retiring, especially in comparison to her bohemian and drug-addled artist brother and his artist pals, the Pre-Raphaelites. But her own life reveals some clues as to her inspiration for her lyrical masterpieces.

Papà - Gabriele Rossetti Mamma - Frances Polidori

She was born in London’s Italian quarter. One of three children, Christina was the youngest child. Their father, a Dante scholar exiled from Italy, was a professor of Italian at King’s College, and their mother, previously a governess, oversaw their education. All of the children were precociously talented in reading, music and art. While the 2 boys went to school, Christina and her sister Maria were taught at home by their mother. Her mother’s teaching would profoundly shape her later work. Indeed, she dedicated almost every book she published to her mother.

No doubt her father's scholarship affected her literary ambitions. He was an obsessive Dante scholar for all of her life (hence her brother's name), writing copious unpublished volumes secularising Dante's writing and drawing out allusions to secret societies and masonic symbols.

Dante Gabriel, Christina, Frances and William at their house in Cheyne Walk, photographed by Charles Ludwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) (1863)

It is no surprise that Christina, Maria and their brother Dante would all become writers of a sort. Their mother’s brother was Joseph Polidori, Lord Byron’s doctor and himself a writer (he wrote the famous Victorian short story The Vampyre), and their father was devoted to his Dante studies. Literature and reading dominated their education. When Christina was 10, the family started a periodical called “The Hodge-Podge”, for which each of the children had to supply a story. Although far from wealthy, the Rossetti’s lived in a sort of genteel simplicity, in a part of London that was a mixed street of tradesmen as well as artists and barristers. With their interesting mix of Italian and English culture, they remained slightly removed from British society - neither fully Italian nor English in their sensibilities or way of life. Instead, they hosted Italian intellectuals and artists at their home.

An unfinished painting of Christina Rossetti, by John Brett (1857)

She began writing poetry in earnest around age 12. In Christina’s early teen years, her father’s health began to fail rapidly. Due to his deterioration, he was forced to give up work, and died several years later. Christina’s mother and sister Maria became governesses and her older brother began working as a civil servant as well. Perhaps bereft of their constant presence in the home, Christina suffered from an ambiguous breakdown from age 15 to 16. Retrospectively, it’s been speculated that she suffered a depressive episode. Others have suggested it was the onset of the Grave’s disease she would later struggle with. Nevertheless, Grave’s disease is a type of hyperthyroidism which can also cause depression and is most common in women and adolescents. It appears as though she went from a lively child to a pious and quiet young woman.

From left, James Collinson, Arthur Cayley and John Brett

Christina’s Anglican faith started to become central in her life, and it would remain so. Over the course of the next ten years, it is thought that she had three proposals of marriages from different men, all failed - mainly due to conflicting religious beliefs. Initially she was purportedly engaged for two years to James Collinson, one of the original Pre-Raphaelites. When he broke away from the Brotherhood due to a crisis of faith, he broke away from Christina as well. In the 1860s, she became close to the scholar Arthur Cayley. However, he was agnostic and this was untenable for her. She wrote a witty and cutting poem, ostensibly about the poet John Brett, which appears to be rebuffing a proposal. It's not one hundred about John Brett, but some correspondence later found would suggest so.

“I never said I loved you, John:

Why will you tease me, day by day,

And wax a weariness to think upon

With always "do" and “pray"?"

The Brotherhood's short-lived periodical, The Germ

At age 18, her poems were published for the first time in the Atheneum Magazine. She also published in the Pre-Rephaelite journal The Germ.

Ecce Ancilla Domini, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Christina modeled for Mary

Christina had a somewhat distant involvement with her brother Gabriel’s artist collective, The Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood. He painted and sketched her likeness throughout their lives, as well as serving as a model several of his painting as well for several paintings by Pre-Raphaelite brothers John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt. Despite Gabriel formally inviting her to join their literary arm of the Brotherhood, Christina refused. It is thought that she was uncomfortable with the exposure this would bring, and which she had no apparent interest in. But she no doubt benefited artistically from proximity to this artist enclave.

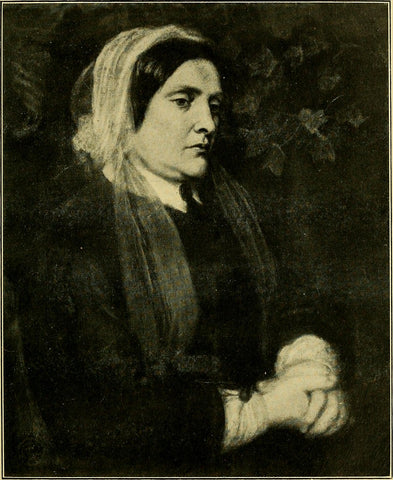

Her numerous illnesses and supposed emotional problems prevented her from engaging much in society, which her apparent introverted nature might have preferred anyway. In later life, she would suffer from Grave’s disease, a type of hyperthyroidism. This rapid decline in health can be seen in the available portraits and photographs of her. Within a few years, she went from strikingly elegant young woman to dour and serious, with the bulging eye-sockets characterised by those suffering from Grave's disease. Precious little else is known about her private life. She systematically destroyed nearly all her family correspondence. Despite her close proximity to her brother’s eclectic circle of artists and correspondence with a few writers, she didn’t care to mix in other literary circles.

Goblin Market and Other Poems (1863)

At age 31, her first collection of poetry, “Goblin Market and Other Poems” was published to much critical acclaim from fellow writers, although brought modest sales. Gabriel and she collaborated on beautiful woodcut illustrations to accompany the poems. The vivid, luscious descriptions were well-suited to Dante's artistic style. In many ways, Goblin Market reads like a Rossetti painting come to life.

An illustration by Dante Gabriel from the first edition

The strange and fantastical narrative poem “Goblin Market” was like nothing readers had encountered before. Its lurid and disturbing imagery cemented her as the foremost female poet of her time. The inspiration remains murky. It might have just sprung from her vivid imagination. Some scholars have surmised she had fallen in love with the married artist William Bell Scott, whose home she had stayed at some months before.

Morning and evening

Maids heard the goblins cry:

‘Come buy our orchard fruits,

Come buy, come buy.’

In the story, two young sisters, Lizzy and Laura, inhabit a vivid fairy-tale world. They are lured to the “goblin market” with the promise of delicious fruit. Laura succumbs to temptation and exchanges a lock of her hair in order to sample the fruit. The poem has religious themes relating to the Eucharist, as well as the salvation of sisterly devotion ( her older sister would later become a nun). At this time Christina also engaged in volunteer work at the St Mary Magdalene Home for Fallen Women in Highgate. It is thought that situations and women she met there may have brought social themes to the poem. She would publish three more volumes of poetry in the subsequent years. These were published in the United States as well.

In 1871, she published a book of nursery rhymes called “Sing-Song”, illustrated by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Arthur Hughes. Lewis Carroll was a family friend and remained in correspondence with Christina for many years. They exchanged books with each other, she receiving, of course, his newly published Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. A keen photographer, he would take several family portraits of the Rossetti family (see above). Both influences can be seen in her popular nursery poems.

Portrait of Christina Rossetti (1877), Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Her later poetry would focus more on devotional and religious themes. Her writings contain frequent Biblical allusions, quotes and proverbs. Her poem, “In The Bleak Midwinter” is now a well-known and Christmas carol. Christina's strain of Anglicanism held a tenet called Reservedness. This was a belief that religious truths should be concealed or hidden from plain view so that true believers would discern it. Her deceptively simple poetry can therefore be understood on several levels.

The Rossetti family grave, in Highgate Cemetery West

At age 60, she moved a short distance away to 30 Torrington Square in Bloomsbury, with two of her maiden aunts. Her mother, sister and brother Gabriel had died several years previously. Her health was very poor, and four years later she would die of cancer. She is buried at the Rossetti family grave in Highgate Cemetery West, along with her parents, sister and Gabriel's wife, Elizabeth Siddal.

"I Wish I Could Remember" Poem, Shop Here

Like many female poets of her era, her writing has been dismissed as somewhat facile and artless. In the 20th century she and her contemporaries received a renewed appraisal. There is still some astonishment that someone who lived a life of relative solitude and piety could write with such unrestrained feeling and passion. But much of Christina’s private life remains shrouded in mystery. Her writing holds the key.

Sources:

In Our Time - Christina Rossetti (Dec 2011)

Quick links

Search

FAQ

Privacy policy

Shipping Policies

Terms of service

OUR MISSION

At BookQuoteDecor.com, our passion is to redefine spaces through the magic of words. We're dedicated to selecting and crafting premium, literature-inspired decorations that do more than just beautify your environment—they honor the everlasting elegance of written language. Our goal is to weave the wonder of books into the fabric of your everyday life, with each meticulously chosen quote.

"Echo" poem, Shop here

"Echo" poem, Shop here

Leave a comment: